|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In addition to exploring gender, this course has engaged with the topic of technology and the impacts that the technology industry has on our realities. I traveled to Austin to explore its rapid tech "boom" and the effects this shift has had on the community.

From Austin’s inception, racial prejudice has been deeply ingrained in the city’s fabric. This prejudice takes many historical forms, from slavery and Texas’s Confederate loyalty to the establishment of I-35 to segregate African Americans from the rest of the city. Today, the gentrification caused by the tech boom disproportionately affects communities of color.

The voices of people of color are often muted in affluent areas and in the technology industry—and the city of Austin is quickly becoming a marker of both. Traveling to Austin, I sought to understand these effects through the stories of individual people who are living this transformation.

I. |

|

|

Two men carrying laptop cases rush hurriedly past a row of huddled transient individuals. Austin’s homeless population has grown significantly over the course of the past few years, and the city’s government expects this trend to continue. Further, 42.4% of Austin’s homeless population are African-American [1]. Though the city of Austin has been progressing and (superficially) improving with the technology industry’s growing presence, there are many populations that have been left behind. |

“One of the challenges of becoming a tech hub is that it generally benefits those who already have a four-year college education, who have objectively ‘more.’ [Austin Free-Net’s] idea is that everyone who wants to use this technology, or is interested in using this technology, should be able to. What we’re really trying to do is develop virtual technology that’s for everyone, in all kinds of communities. And our challenge right now is to establish ourselves as a trusted resource outside of the East Side [where more and more minority and low-income communities have been expanding].”

|

|

II. |

|

|

A security guard stands by the once-iconic Castle Hill graffiti park. The park, formerly an open space for public artistic expression, is scheduled for decimation in preparation for the construction of a more polished “graffiti park” facility. Some equate this construction as a symbol of the “paving over” of Austin’s once-organic and accessible art scene. |

|

The graffiti-d phrase “R.I.P. Austin” counters the no-trespassing warning beside the closed graffiti park. Many Austin residents see the closing of this park as a symbol of the gentrification of not only Austin’s neighborhoods, but also of its culture. The city’s lively arts scene, in many ways made what it is by artists of color, is being forced out as the tech industry transforms the city. |

""The big challenges for artists in Austin include space. Gentrification is not only displacing marginalized communities, but also artists. Art — the same thing that made this city’s reputation, that made SXSW what it is — is diminishing. Tech is displacing art.”

|

|

III. |

|

|

A mural on the East side of I-35 proudly proclaims “East Austin pride.” East Austin, formerly comprised of segregated Black and sometimes-Latinx neighborhoods, has seen an increasingly dramatic demographic shift during the expansion of the technology industry in Austin. Properties in formerly all-black neighborhoods, treated as “dangerous” by white residents, are quickly being bought up by the many people moving into Austin [2] — and, as a result, the costs of living in these areas are quickly becoming unsustainable for many of their more long-time residents. |

“We've got nothing. This doesn't really count as a place, you know?”

|

|

IV. |

|

|

Lucas, an artist and Austin resident, talks to Shelby, a woman who works for Six Square, about the history and significance of the Six Square cultural district. More and more neighborhoods like this one — cultural and residential centers for people of color — are being altered and disappeared as the urban landscape of Austin continues to spread outwards from its center. Six Square was formed by the city in 1928, when segregational policies forced Black residents to live within a six-square-mile boundary [3]. Today, it is maintained as the heart of Austin’s Black cultural Renaissance, and its residents work tirelessly to resist the gentrification that sweeps the city. |

“Growing up here, I've seen a lot of gentrification. That’s why Six Square is so important — it’s about preserving what’s left of the Black cultural Renaissance that was here in this neighborhood. Nothing that we’re doing [to combat gentrification is a waste of time. In that effort, it’s effective… We’re trying to keep these pieces alive.”

|

|

V. |

|

|

A statue plaque at the University of Texas quotes Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s most well-known reprise: “I have a dream.” The achievements and struggles of the African-American community are undeniably a part of Austin; likewise, the actions of white city officials and residents alike, which have historically and systematically disadvantaged Black people, cannot be ignored. This “cycle of wrongdoing” and “gestures to ‘make up for it’” continues today as social programs and public resources struggle to support these communities. |

“I-35 was built quite intentionally to bifurcate the city. Even though segregation ‘on the books’ doesn’t exist [today], it’s still strong in things like Austin’s zoning policy. There’s a cycle of wrongdoing and gestures to ‘make up for it’ in Austin. [The establishment of the African American Cultural Center] is one gesture to preserve some of what’s being lost throughout this process of gentrification.”

|

|

VI. |

|

|

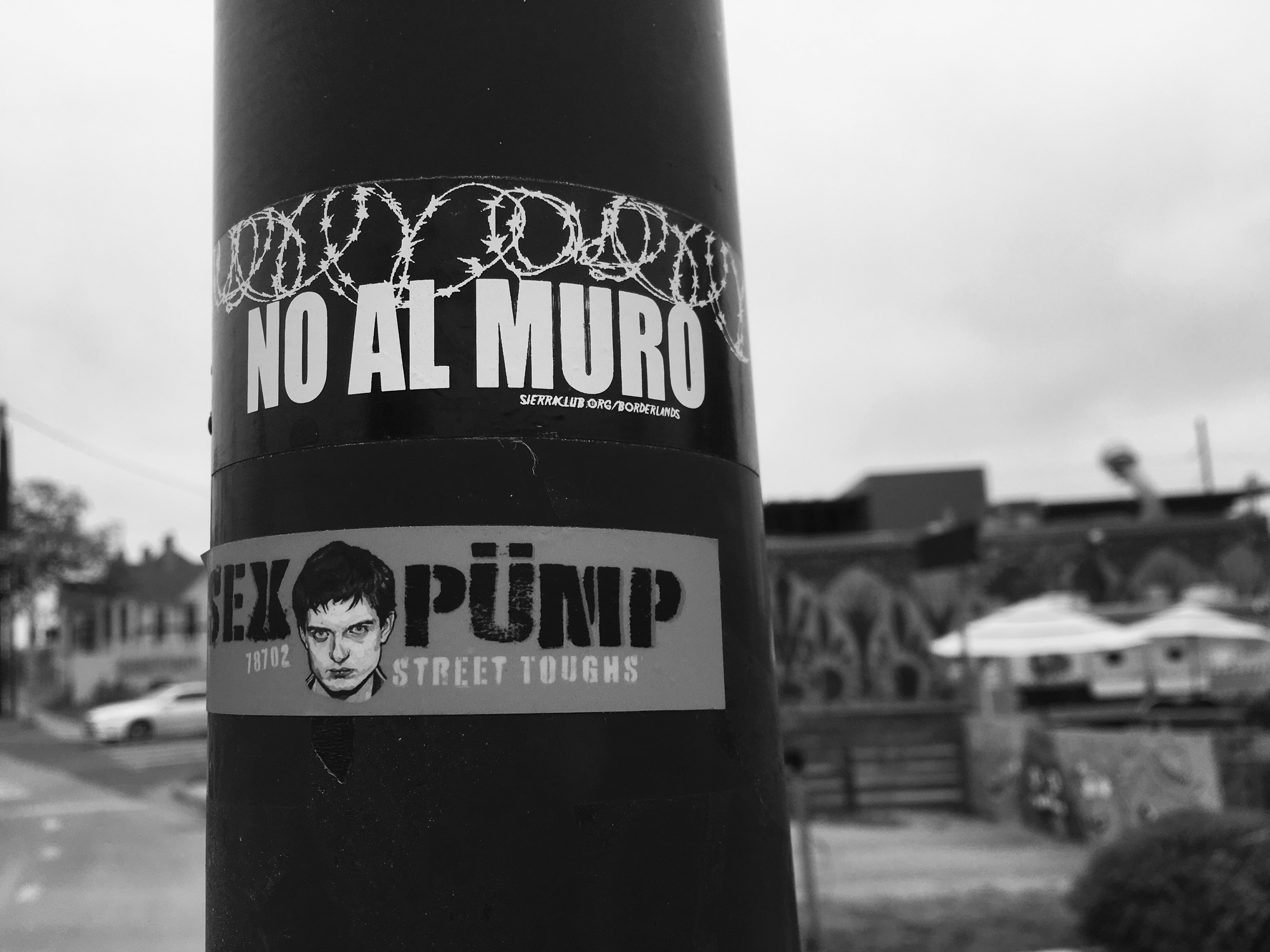

A sticker on a lamppost on Rosewood Avenue, placed at a point of visible change between the struggling East Side and the newly- and heavily-gentrified sections of the avenue, reads “No al muro” (“no to the wall”), evidently a reference to Trump’s proposed border wall. As technology and hipster culture pour into Austin, a superficially-progressive and left-leaning political alignment has begun to color the city blue. However, while Austin’s residents are hyper-aware of the ongoing crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border, few seem engaged with the very real border that bifurcates their own city: I-35 and the history of segregation which surrounds it. |

“It's hard to scale emotions proportionately to a large group of people. As we become more urban, that lifestyle needs to be combined with strategies for purposeful connection. We have both a moral responsibility and an opportunity to practice empathy and align it with our personal values. [We need to] empathize on purpose especially when it’s hard.”

|

|

VII. |

|

|

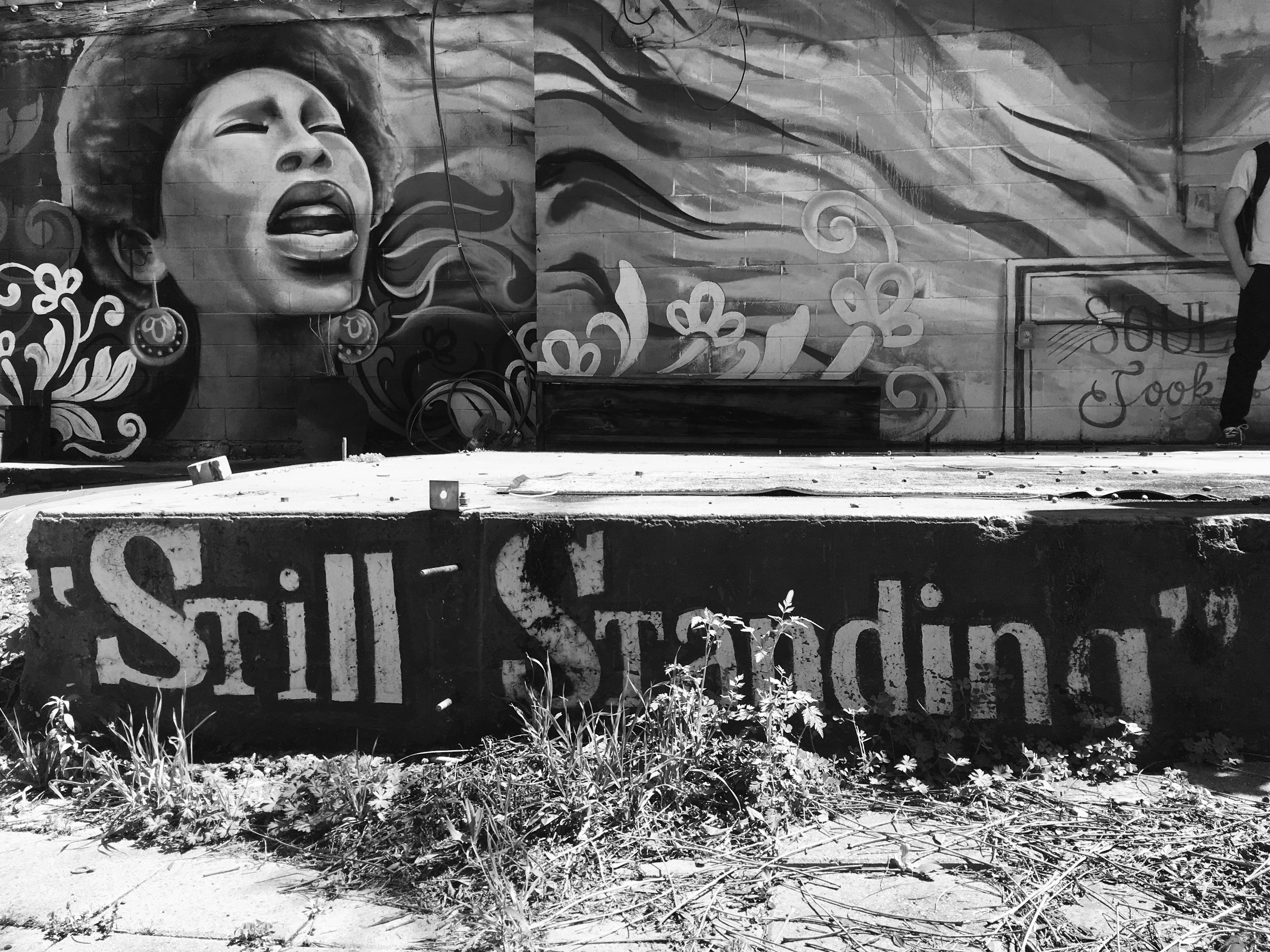

A mural on the recently-closed historic Victory Grill proudly proclaims “Still Standing” — in reference, perhaps, to Austin’s Black community, to the arts in Austin, to residents of the East Side, to all three. Ironically, however, the Victory Grill — founded in 1945 to create a space for Black soldiers to gather upon returning from the war — recently closed in the face of growing gentrification. The rise of tech (and the heightened cost of living which it brings) has forced the Victory Grill’s removal, just as it has displaced much of Austin’s art scene and neglected its communities of color. |

“I-35 was built to segregate the city. Historically, Black and Latino communities would live on the East Side, and white Anglo-Saxons would avoid that area. Now, how can people from those communities, and people from service industries and creative industries, afford to live here anymore?”

| |

VIII. |

|

|

An art installation above The Contemporary Austin reads “With liberty and justice for all.” This message rings through downtown Austin, an increasingly progressive city, on bumper stickers and political yard signs — but, for many of Austin’s residents, it has never rung true in practice. While Austin’s growing status as a tech hub benefits the city’s government, businesses, and many affluent residents, many communities — primarily those comprised of low-income residents and people of color — have been left behind or even forced out of the city altogether. |

“We need to have more conversations about the institutionalized racism that’s here [in Austin]. The most important thing that we can do as white people is to think about how we contribute to that. We have not honored diversity in the United States in the way we should have. Change is good — for a city, for people — but you need to have growth that ‘raises all boats.’ When you grow a city properly, you want to raise everybody. Austin, Texas has never done that. Ever.”

| |