Bodies of Water

(& Bodies, & Water)

What the Women Told Me

or Women's Words, Women's Work

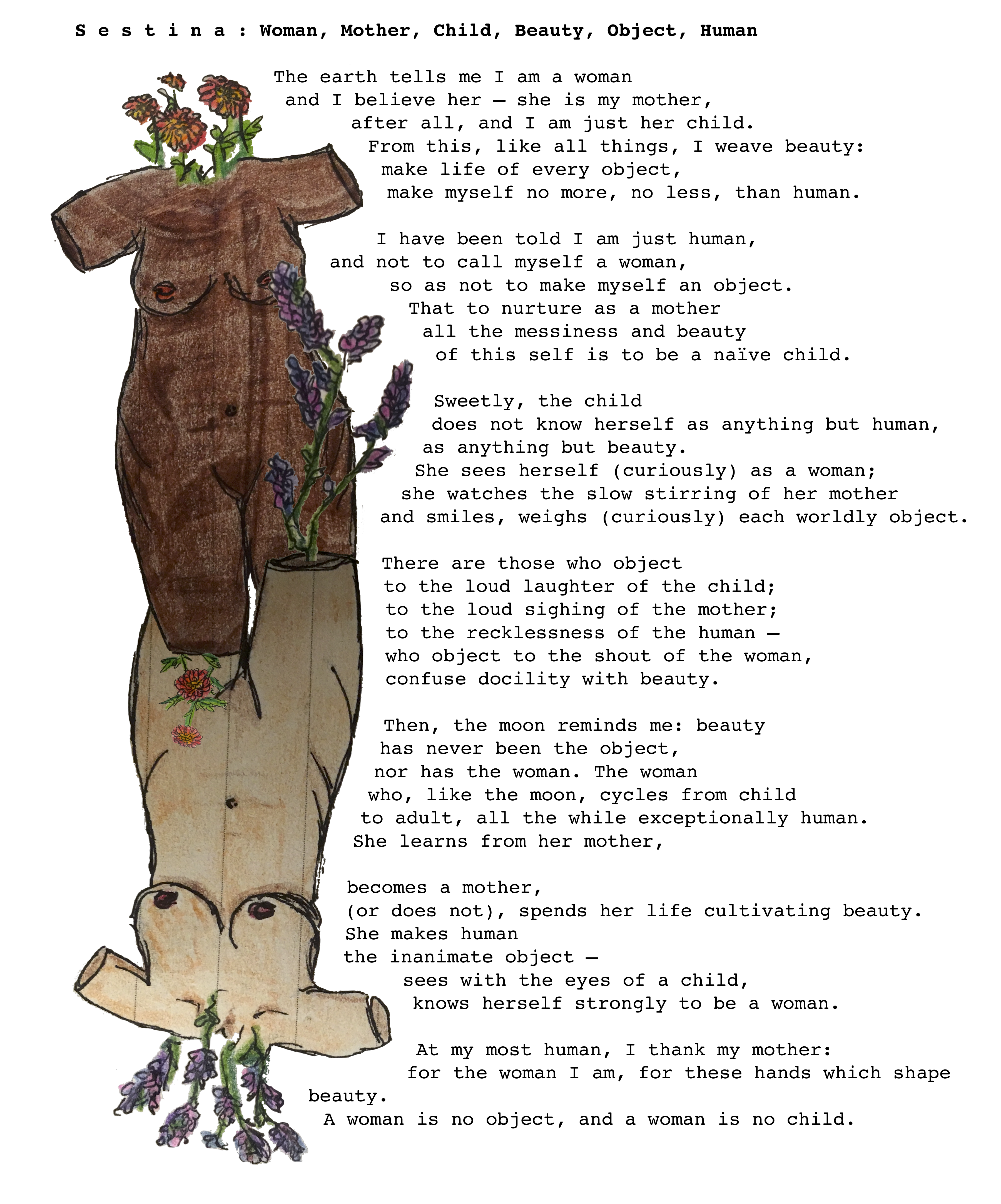

S e s t i n a :

Woman, Mother, Child, Beauty, Object, Human

About these poems

"Bodies of Water," written in free verse, aims to capture the image of the "wild woman" archetype, most recently made famous in contemporary feminism by Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estés's Women Who Run With the Wolves. "Bodies of Water" paints the wild woman as analogous to bodies of water — bodies that are both incredibly powerful and incredibly nuturing. The persistent and forceful nature of the wild woman is what makes her so compelling, but her relationships — with nature, with family, with time, and with herself — are just as vital. "Linked from riverside to mountainside," they are what allow her to "continue, / & to change, / & to carry."

"What the Women Told Me" alludes to five influential female poets — Mary Oliver, Maya Angelou, Kay Ryan, Sarah Kay, and Emily Dickinson — and some of their works which touch upon feminine identity. These poets, among others, have all been deeply influential on my understanding of both womanhood and poetry.

"S e s t i n a" is drawn from a number of words which describe the woman of Betty Friedan's "feminine mystique" (Specifically, "mother," "child," "beauty," and "object," which are contrasted against the general, more fully-formed and flexible identities of "woman" and, ultimately, "human"). The Feminine Mystique, a seminal feminist text published in 1963, is often credited for sparking the inception second-wave American feminism. "S e s t i n a" seeks to expand upon the idea of the mystique through the relationships between human and nature, mother and child, and person and object.